Get Free Guides To Ascension & Global Consciousness

My first experience in Israel was a coming-of-age story in countless ways. A bohemian spirit, I had come to know a unique way of life, a far cry from the one we’ve been conditioned to seek in the West. It was during my formative years that I lived on a far left Zionist kibbutz, a fact I didn’t know when I first arrived.

It’s not as if I didn’t know anything about Middle Eastern history or the Jews’ horrific past; however, I was surprised to find a country filled with immigrants from Latin and South America. The kibbutz had myriad accents and languages beyond Hebrew. Beyond English. And like me, they were misfits and because of it, we bonded in deep ways that had nothing to do with Israel and perhaps everything to do with Israel.

Nearly all of my encounters were with misfits who were on a journey to find themselves and somewhere they could call home. They came from nearly every corner of the world, had a wide range of belief systems, and ranged from 18 to 85 years of age. We were all escaping from places we didn’t fit in only to discover we were escaping from – rather than embracing – ourselves. While part of this journey was a coming of age story, at least for me, another part of it was about running from our wounds for so many of us.

I had very little money as a teenager bumming around Europe and later the Middle East. It seemed natural for me to get the cheapest ticket available to board a boat in Brindisi Italy bound for the Israel coast – Haifa to be exact. And so, I bought a ticket they called cargo class, which meant a seat on the floor of the deck with the animals. Yes, really. It wasn’t the first or last time I made such a decision to save a buck.

I’ll never forget our arrival at the port of Haifa, for the land felt so foreign compared to the European port towns I had explored for so many months. Since my ticket entitled me to deck access only, that’s precisely where I slept all night — on the open deck leaning up against my backpack. Alone. I was freezing by the time dusk arrived and there was cool mist in the air.

As the boat approached Haifa, I was amazed how many military ships surrounded us as we docked and how many army uniformed men with guns slung over their shoulders were on the ground when I disembarked. I clearly wasn’t in Kansas and although I didn’t have fear, I was much more alert. In fact, I recall moving my money belt under my ridge of my jeans and double checking the security of my bags.

I knew very little about the country, didn’t have a guidebook, map or any contacts except for the address of an exchange student we hosted at our high school who lived somewhere near Tel Aviv. I had his snail mail somewhere; remember, there were no cell phones or email in the eighties. Nor did he know I was coming to Israel because I didn’t know I was planning to be in Israel.

You see, I really didn’t expect to ever live on a kibbutz. Truth be told, I was searching for a British guy I met on my travels in Europe who said he was on his way to Israel to find work . . . on a kibbutz. We had a bond, or at least that’s how it felt at 18 years old when everything and everyone is vibrant, alive and timeless. At a time without cell phones or any other way to communicate, I managed to find him. How you might be wondering? The only information I had was that the kibbutz was along the coast, so I hitchhiked south from Haifa and stopped at every kibbutz on the water. I was a bit intense in my youthful years, with boundless energy and no task seemed impossible. He had landed at Kibbutz Zikim and I found it (and him).

Zikim is south of Ashkelon along the western coast, less than a kilometer from the Gaza strip. I didn’t realize at the time that 99% of western volunteers who worked on a kibbutz set it up from their home countries months in advance. It was typically a lengthy process but I wasn’t about to let that stop me.

When I got to Zikim and asked to volunteer, I was immediately rejected until they learned I knew one of the volunteers. (yes, he vouched for me). This seemed to help as did my suggesting I’d give any job “a go.” That said, they didn’t have space for me for two or three months and I needed a recommendation. I would later learn a lot about agriculture, farming and community life, but first, I had time to kill and a letter to secure . . . from someone (or place) they’d accept. With that in mind, I set off.

I ventured further south, then northwest and then east, mostly alone with my middle finger pointing down to the road, signaling I wanted to be picked up. I covered nearly every inch of the country. Open air trucks were my favorite since I could feel my hair blow behind me in the wind, a reminder of how free my lifestyle was and that nothing was between me and the trees and birds but the wind.

It took courage and resilience to hitchhike for days on end as a foreigner, especially as a woman traveling alone. Hitching in Israel was different than it was in the states. Instead of throwing your thumbs up and back, you used your forefinger and pointed it down to the ground. At the time, it was an easy and inexpensive way for both army soldiers and civilians to get around. In other words, it was common.

Locals imparted three rules: First, don’t jump into an army truck with black plates. Second, don’t hitch when Arab cars or trucks drive by – the blue plates, and third, don’t wear sparse clothing if you’re traveling alone as a woman. I was constantly warned about the possibility of getting raped or kidnapped. In my pony tail, shorts, and torn t-shirts, with a knapsack on my back, I successfully made my way south along the coast.

Hitching back then wasn’t just about getting from point A to point B – it became a way of life. Sometimes the back of a farmer’s truck became my shelter for the night and other times I’d just jump into a car to hear a new story. It was always an adventure and oddly enough, I never had any fear. You have to realize that I came to Israel on a whim, curious to experience the country after hearing a riveting story about kibbutz life in a café in Athens. And of course to see if I could find the cute British guy I traveled with in Europe for a week.

When I reached the far north of the country, I ran into Mario, a German hippie who said he had an in to a kibbutz along the Galilee. Twenty-two year-old Mario was easy to follow since he had medium length dirty blonde wavy hair, a sexy accent and wore a small black cloth backpack and a guitar on his back. Together, we headed to a Galilee kibbutz and if it was full like so many I had encountered in my first couple of weeks, we’d merely ask for a piece of land to pitch our tent for the night.

As we made our way through the entrance on their dusty unpaved road, a rooster was crowing in the background, two dogs were barking, at least a dozen stray cats were fighting and hissing alongside us, and in the front of the kibbutz volunteer supervisor’s door, hundreds of tiny ants zipped back and forth in straight lines and then around in circles as if they had suddenly lost their way. Or perhaps they were merely disrupted by two human beings who unexpectedly showed up.

After the kibbutz rejected us, we set off close to dusk. While it was too dark to hitch, Mario was eager to make it across the Lebanese border within the next two days since he was convinced we could land jobs picking olives in the south. Here, we could remain hidden from the world for a long time. He was irresistible and I was 18, so how could I say no. I was curious to explore Lebanon (curious enough anyway) although I was also fixated on finding a temporary home on a kibbutz before crossing any borders. That said, we made our way to the border quite by accident – on foot late at night. As impossible as it sounds given the tight security, we slept three hundred yards or so off the road on a dirt patch under a full moon. Whether it was a gift from the moon or simply youthful luck, grace was on my side often in those bohemian days.

The next night, we set up camp using a tiny flashlight and the light from the stars. He sang about revolution until I fell asleep on sharp rocks until the cold waters from high tide brushed up against the side of my sleeping bag and abruptly woke me up. We had apparently planted ourselves between a banana plantation and a beach, but since we could barely see a thing when we set up camp, our surprise only came at daylight.

With sad eyes, I left scruffy rebellious Mario a few days later, the man who reminded me at times of Christopher Atkins from the Blue Lagoon. He went north to pick olives in Lebanon and I headed south to pick fruit on some kibbutz. Hopefully Zikim.

Someone along the road suggested I could get a recommendation letter from the official kibbutz office in Tel Aviv. En route, I met British Shaun, who was half Swiss even though he didn’t seem to have an accent from either country. It wasn’t the only thing displaced about him and later, I would learn we were both misfits on a vision quest of sorts and our passion for culture and language was a strong commonality that bonded us.

Along the way, Kibbutz Nizzanim turned us down although they put us up for a couple of nights and we shared whiskey, tequila and traveling songs with the volunteers until dawn. We then headed to Ashdod in the back of a truck with cages and cages of squawking chickens. Here, we managed to land a bartender and waitress job at an Israeli Irish pub. The place was so eclectic that the employees spoke more French, German, Polish and Russian than Hebrew and English despite its roots.

The entire wait staff stole food from the pub’s fridge every night, but given how little they paid us, it was the only way to survive. Times were tough then. The economy was tanking, and while it was affecting Israeli commerce, it was also affecting kibbutz life. Budgets were getting slashed and volunteers were being turned away, including some who had an official letter from their home country and arranged everything in advance.

Shaun and I set off once again by foot, this time to Moshav Ashue near Beer Sheeva to track down a farmer who owed him $200, a fortune in those days. Remember that we existed on $4-5 a day. A day’s spend would look something like this: 75 cents for Raita with cucumbers, another $1.25 for humus and tahini on a pita and $2 for a mattress on a floor in a hostel or brothel-like hotel, always in the poorest part of town. Before I met Shaun, I traveled with another Brit and we rented two mattresses on a rooftop in old Jerusalem for close to a month for a mere $1 each. We were each given a soggy mattress with a sheet and access to a cold-water tap for washing and laundering our clothes. We could hear rats scurrying past us in the night so I rarely opened my eyes when nightfall came for fear of seeing one of them nestled on my sleeping bag like a purring kitten. It worked for us. I was 18 and he was 21. Life was simple, we had no fear and very few needs.

Looking back at my handwritten diary from that time, I was surprised how much I spoke of survival. Money was always tight and the jobs I picked up along the way paid so little, I barely had enough to cover a roof over my head for the night and one meal a day.

It turns out that Shaun never managed to get his moshav farmer to fork over the $200 he was owed. While you can make more money on a moshav than a kibbutz and people have a right to own their own land, the work is brutal and the hours are long, often in blazing 100-degree sun. My ex-husband worked on a moshav in the same decade and his farmer apparently worked him twelve hours a day with only one day off.

We had a hard time getting there since it was in the south and you couldn’t trust just any license plated car as you got closer to the Egyptian border. We finally flagged down an army truck, where we nestled in the back between smelly rayon bags and a worn tire until we got close enough to a junction where we could walk the rest of the way. It turned out to be a long walk under a hot blazing sun.

After our failed attempt at the moshav, we headed to Yad Mordekhay, the largest kibbutz in the area. They too turned us down; while she adamantly shook her head no over and over again, she went on and on about a boisterous English volunteer who damaged so much property from his drunken escapades that people were still talking about it nearly a year later. Simply put, they didn’t trust western volunteers.

In Palmahim, we slept on the beach for a couple of weeks and lived off pita bread and water, a regular staple for us. Once we got to Kibbutz Zikim, I was so tired from nearly four months of road-life, that I pleaded with the Kiwi-born supervisor for a volunteer slot, suggesting I would do anything. She told me to return in another three weeks. Relieved, I followed Shaun to Ashdod since he could get his hands on a free apartment in exchange for pub duty. What my buddy Shaun failed to mention was that there was no electricity or gas, which meant no heat, hot water, stove or lights. Dark and filthy, but it was a free place to lay our heads at night for the next three weeks and we had jobs tending bar.

Here, we met Aeriole, a large wealthy gay designer who also claimed to be a British Lord. When he wasn’t designing people’s houses, he was predicting their future through cards and stars. He told me that if Zikim turned me away when I returned, I should head to Kibbutz Ginnosar. I always looked forward to Aeriole’s visits. He would glide through the apartment daily with his ‘Oh Daaaarling wonderfulssss”. His large colorful body would bounce past us and then into the kitchen where he’d sit at the kitchen table. I’d follow him in and marvel at his readings as he went on and on with so much certainly. In hindsight, I wish I wrote down what he said.

By the time I was ready to hitch back to Zikim, my funds were down to $43. I began to do the math and realized I’d have to remain on the kibbutz for a while to allow enough time to put plan B into action, one which obviously brought in more cash. That said, I was resourceful in those days . . . you could say I became a master at existing on very little food and getting free lifts. Over the course of eleven days, I managed to get by on 58,740 shekels, which equated to $38.50 at the time. If there was one thing I was a natural at, it was making my money stretch further than anyone else I traveled with, except for maybe Shaun who seemed to get by without even the basics, including shampoo or toothpaste.

Shaun and I returned to Zikim together and there were finally volunteer slots for both of us. Like me, he was a master at not giving up despite difficult odds. Thankfully we were young and resilient, for rest assured we worked hard for our keep.

During my first week at Zikim, I made friends with dozens of locals from various parts of the world, including Hungary, the Czech Republic (Czechoslovakia in those days), East Germany, Latin America, and South America, all Jews, who fled to places as far away as Chile during the Holocaust before moving to Israel some ten and twenty years later. The volunteers were equally eclectic, each of them running from a place they didn’t feel they belonged. We all shared that in common. Every night, I sang songs in the kibbutz pub with Danes, Dutch, Brazilians, Swedes, Brits, Aussies, Kiwis, and Germans. We danced often. And drank. Someone was always pouring beer, so whether you drank it or not, your glass was filled. There were theme parties and various activities you could partake in almost nightly. Note: the kibbutz photos are in rough shape largely because they were taken on a small, cheap camera.

Somewhere along the way, I lost my t-shirt, shorts and pony-tail look and adopted Birkenstocks, the most feminine ones I could find naturally and long flowing skirts, tiny braids with ribbons and toe rings.

The first volunteer I met was sexy Jacque, an overpowering Brazilian who always had to be in control, largely of the women in his life. Almost daily, he invited me to run away with him to Eilat, all expenses paid, an offer that was easy to refuse despite his charming ways. Dimitri, the only Greek among us, was a quiet guy with a passion for the piano. We alternated playing for each other in the downstairs mess hall cafe, which is where we met Sybally, my favorite kibbutznik Israeli. Although he was only 47 at the time, he became a grandfather-like figure for me. We loved talking about philosophy and down the rabbit hole we’d go almost daily, he with his ideas, me with my own. Others would join us from time to time and the debates often became heated. Then Sybally would loan me his tennis racket and encourage me to release the built up energy so I wouldn’t spend too much time in my head.

Dimitri was asked to leave not long after I arrived. Apparently he wasn’t so quiet when he drank vodka; it turns out that he was caught throwing himself on a barbed wire fence and driving a tractor into a pole. Everyone has their quirks as all misfits do and reckless driving happened to be one of his.

I was led to Room 7 in an area of perhaps a dozen rooms or rather ‘small square wooden shacks’ is more accurate. These shacks that each housed one room were attached to each other in a bushy area filled with straw and bamboo shoots. In between these shacks lay what us volunteers called Main Street, an open area that was wildly overgrown.

To give you a fair visual of our sleeping quarters (above), imagine a string of rustic beat up wooden shacks, all glued together in a row. Each shack was a 10 by 12 room that was connected to the next one. There was nothing separating them but weeds, straw, grass and bamboo shoots were abound. After one late afternoon group effort, we managed to chop enough weeds down to hang a clothes line built out of rope and sea shells. The showers were outside, one for the girls and one for the boys. If you’ve ever seen the outdoor showers in the Mash re-runs, you’ll have a pretty good idea of what the volunteer shower stalls looked like.

Frogs often clung to the side of the wooden beams, crickets could be heard day and night, and it wasn’t uncommon to find a snake (dead or alive) on the way back to your room. The entire area was so flooded with stray cats, we couldn’t feed them all. Many of us would steal milk from the kitchen to keep them alive but not all of them made it. If I’d go to the fridge at night, I’d have a couple of dogs and at least a dozen cats following me.

I barely saw Shaun after we were assigned rooms and jobs. He headed off to the orange fields and I went to work in the Polyron foam factory. Once booze was widely available, he drank heavily every night, but he wasn’t the only one. When I’d bump into him, he’d share the gossip on everyone and everything from all the neighboring kibbutzim. It turns out that he created a successful albeit bare bones snail mail version of match.com between all its members and our volunteers. It was amusing to watch Shaun orchestrate it.

In the late afternoons after I’d finish up at the factory, I’d often take a shower if I didn’t head to the beach. There were bird nests above the showers, so it was pretty common to have a bird or two fly past your breasts while you were soaping up. When one or more of the girls were showering, the horniest of the volunteers, Kim and Chris would bombard the shower area with buckets of cold water, which was a bad idea since we had a water shortage. Both our showers used the same tank and it didn’t take long before it was empty. There was a convenient outdoor water tap at the end of Main Street, which we used to fill our water bottles or brush our teeth at the end of a long night.

Although I worked with two Brits in the foam factory, they couldn’t be any more different. London-born David looked like a blonde version of Italian Fabrizio Venturi who I went to high school with in South Africa. Casual, sweet and a lady’s man, he was constantly talking about the dream job he was going to land next year. Richard was tall, muscular, black, and handsome. He had that rock star thing going on. Unlike urbanite David, Richard came from Bristol, the same industrial city as my buddy Jo – if memory serves me correctly, we got tossed off an Egyptian train with in the middle of the night for buying the wrong ticket. Everyone had a long eclectic history of ancient cultures and lands. We spent time gabbing about the locals, what we wanted from life, and more efficient ways to pack foam.

Then there was Norweigan Dan, who flirted with the local women as well as the volunteers. Flirting was his go to, which annoyed Swedish Jan who referred to Dan as a wimp since he didn’t have the courage to make a move. Jan wrote poetry and sang sappy songs on his guitar in his room while the other Swedes were getting drunk in the kibbutz pub. Before he came to the kibbutz, he had a job playing the piano at the Queen of Shiba somewhere in Israel. When he quit, he bought equipment for a 20-pound note and took to playing on the street. His room was three doors down from mine so I could often hear him when I crawled in around 2 am, down for my two or three hours of sleep before we all had to be up for our morning jobs.

We started at around 5 am at Polyron and our jobs consisted of packing foam on a conveyer belt for eight hours a day. We all wore uniforms, which were never warm enough for those early morning walks to work. I used the points I earned to buy two uniforms in the kibbutz shop, so I could double up. I longed for a role that would start later when the sun had already warmed the sky and finish before it sank behind the horizon.

The sunsets didn’t have Arizona’s intensity but they were set against a tan dry landscape, which gave them an air of ancient drama. I frequently ran into Scottish Stuart at sunset, which if I wasn’t horseback riding with Israeli-born Asaf, I was walking back along the beach path, where you could quite easily see an army truck or danger hazard sign along the way. I never discovered what the closed off areas were used for – frankly, I figured life would be less stressful if I simply didn’t know.

A few of the horses were wild and Asaf was on a mission to break one of them in before I left. Sometimes I’d watch him in the late afternoons get tossed off the back of one. He’d look up at me, grin, pick himself up and start again.

At 41, Stuart was the oldest volunteer on the kibbutz and from what I could tell, he would still be wandering around the world living from paycheck to paycheck at 50. He didn’t believe in banks and said if he ever made enough money to save, he’d keep his stash under a secret board no one could find. I guess he never thought about house fires, attic rats or mold.

Unlike the younger blokes, as Australian Chris and Kiwi Kim would call them, Stuart largely kept to himself and never hit on any of the kibbutzim women or volunteers. The northern European men were fairly tame until a boat of female Swedes arrived several months later and our volunteer pool became suddenly imbalanced. Late night sex and alcohol were inevitable in a place filled with coming-of-age foreign and Israeli misfits and a boat-load of Swedes. Blonde-haired British Sue introduced me to the pill which she took for her acne. I too learned that it solved the acne problem and was so appreciative that I became her fashion diva. Before her make over, she wore conservative denim knee length shorts and flowered t-shirts. Needless to say, she became more glamorous and my skin glowed.

I had too much New England in me to sleep with various volunteers and locals every night and was a hopeless romantic to boot. That said, the Swedes were always having sex — with each other, the Europeans, the Aussies and the local Israelis. Rikka and Monica taught me nothing about birth control but everything about detachment, holiday flings and Stockholm. Years ahead of their time, they were in and out of a new fling every 24 hours. For them, sex was like food. In the morning, they might prefer yoghurt or French Pierre and the evening lamb or Irish Mick. They sure seemed to have a lot of fun.

A woman charmer, Dublin-born Mick always had a tragedy following him, in the past, in the present and somehow you could see it in trailing behind him in the future . . . forever clutching to him like a long lost friend. Mick attended more funerals than all of my grandparents’ friends combined and according to his stories, they all seemed to be held outdoors under umbrellas. No wonder there are so many Irish movies with wet funeral scenes. He took life as it came and it always came gradually. Because of his belief in a slow, casual and simple life, he was a great listener and writer. He shared amusing tales with whoever would listen and they were always funnier after margaritas and Genesis or Rush playing in the background. In a pre-digital world, we listened to our favorite bands on cassettes from an old tape deck Kim brought from Auckland.

Surrounded by farmland and factories, there was a dearth of clubs and entertainment so we simply created our own. Since Shaun was running an inter-kibbutz dating operation, he knew someone on the neighboring kibbutz who had access to an army truck. Vehicles were not allowed on a kibbutz, so it was a godsend when someone found a car, truck or tractor we could secretly borrow for an errand or an evening.

We used a truck occasionally to visit nearby kibbutzim on their designated movie nights. Suddenly, there was even more sex and alcohol, particularly among the Swedes and the two new Belgian volunteers Freddie and Lauren, who was short and stocky and owned a pair of orange, red and purple striped shorts we all wanted to burn. If you ended up missing your lift back to Zikim, you were stuck hitching or borrowing a horse the next morning. I experienced both. Life was simple but we had all grown accustomed to living each day that way.

The kibbutz had approximately 300 members at the time and was apparently in debt long before we arrived. There were no boundaries or titles. The philosophy was purity on this pro-Zionist kibbutz, where the accountant and others with professional titles took turns washing dishes once a month. I was transferred to the kitchen for a while where not only did I wash dishes, but peel onions for a few hours a day.

German Aloff was the one who kept my spirits high and made me laugh when my eyes were burning from ten pounds of onion-skins. He never joined a group activity; when he wasn’t working, he was trying to learn Russian so he could soon follow a flame to New York where she was working as a cocktail waitress without a visa.

The locals didn’t really join in our festivities but I frequently joined in theirs, whether it was rehearsing a play, participating in board games, team soccer and volleyball, or singing around the piano. Sometimes I’d just hang out and talk to them while their kids ran around the field. There were also the adorable Israeli South Americans.

There were two kinds of kibbutzim at the time – those who believed that children should live in the same house as their parents and those who had a separate “children’s house,” where the children would eat and sleep and someone other than their parents would be assigned to take care of them. Zikim adopted the latter, which later became controversial among kibbutzniks. My friend Hagai grew up in a children’s house on a kibbutz near Beer Sheeva and he talks about lonely nights where he longed to see his parents.

I would sit with mothers and chat about life while their children would romp around the grounds. Some of these mothers were Holocaust survivors but they never spoke of the past. In fact, no one did. We all avoided the past and our emotions although we did spend many memorable hours telling stories.

There were Israelis who popped in and out of our conversations, like Jerusalem-born Toby, who was a female Jesus if I ever saw one. A radical hippie, I heard she changed her name, which wouldn’t surprise me. Sometimes she would show up at the foam factory with her pal Omer who was in the middle of his two-year army stint. Usually Omer was in uniform with a gun slung over his shoulder but other times, he’d be in cotton pants and a white t-shirt. Through Omer, I met 18 year old Sivon Cohen who showed me around Beer Sheva. If I recall correctly, we also danced to Journey in her backyard until 5 am.

Beth arrived after I did. She competed with me daily – in the kitchen, on the tennis court, in the ocean — you name it. We barely talked since her glares were so uncomfortable I simply avoided her. I later learned she was beaten as a child and ran away from home at 17. A misfit like the rest of us looking for family and somewhere we could call home, Zikim filled that hole for her and so many of us. After a couple of months, the competition dissipated and she was just Canadian Beth with a wounded past and a sweet smile.

Perhaps Mario should have followed me to the kibbutz rather than heading to Lebanon to pick olives alone. He wanted to get lost for a long time and kibbutz life allows that if you want it to. It was easy to get lost on a left Zionist kibbutz like Zikim. While our stories and histories were all so different, we lived with hundreds of other misfits who cared for you, comforted you, and listened when you needed a friend. We also lived close to a beach, the weather was ideal and we never worried about having a roof over our heads or finding a healthy meal. Breakfast buffets exploded with pita bread, various kinds of yoghurt, tomatoes, avocados, eggs, raw vegetables, herring, salmon and olives.

While everyone worried about a shortage of water, there was never a shortage of food. So we all lived a life where we felt lost, and most of us didn’t want to be found. I remember calling the states every couple of months or so from a pay phone and it was the only time I ever had contact with the West. Because my funds were so limited, the calls were pretty short and I was more than okay with that.

I’d often day dream while I was riding. Trotting along a stretch of beach without another person in sight was nothing short of pure bliss.

I dreamed about what I’d become in the future — who I’d become. Perhaps I’d change my name to Angela or Michelle. As Angela, I’d become a prize-winning photojournalist who wrote about environmental issues. As Michelle, I could model in Paris and share riveting stories about my Hungarian parents. At 18, I was a vivid dreamer but I suppose that goes with the age.

While we were based in an area of the world that was constantly at war, we lived in the moment and rarely stressed about Palestinian bombs or Iranian missiles. Such stresses were hardly small stuff, but we also realized we couldn’t change things we couldn’t control. We weren’t citizens so it was our choice to be there and the longer we stayed, the more bonds we made.

My neighbor could have written the intro for Don’t Sweat the Small Stuff. Copenhagen-born Soren was a freckled, tall skinny strawberry blonde who lived in the shack next to mine. He lived in a bright blue logo-less sweatshirt with jeans and sandals. (see photo above of Soren standing in the foam factory). The walls were incredibly thin so your daily chatter became your neighbors and theirs became yours. We didn’t need a body of water nearby to hear the echo of other people’s conversations. They were constant as if we were all living in a small ghetto where everyone’s doors and windows were open to each other and the world.

Smoking was common back then. In fact, all the volunteers smoked cigarettes except for Soren and me and many smoked marijuana as well. Pot wasn’t a daily thing, except for Tanya from Holland. I liked nearly everything about her: the way she dressed, the perfume she wore, her wild hair braids that changed almost daily, her small heart tattoo on her cheek. I longed to have a meaningful conversation with her but she was too stoned all the time for me to ever make sense of what she was saying.

Each volunteer made $25 a month and this money would be spent on day trips to nearby Ashkelon (or Ashqelon). We could hitch to the coastal city in less than an hour. What we didn’t get in cash, we received in points, which we could spend in the local shop. My points were typically spent on a new uniform or toiletries.

After many long weeks packing foam, Soren and I were transferred to the nearby Polyrit Factory, which was still standing when I returned to the kibbutz roughly 14 or so years ago, but it was no longer used to produce cheap Italian shoe soles and computer parts. Instead it produced car accessories. We referred to it as the glue factory since Soren and I were assigned the glue belt. Starting at 5 am with nothing but a beat up AM radio and our morning biscuits and tea, we glued shoe soles for eight hours. As tedious and loud as it was, working at Polyrit was still preferable to having to sand parts and pack foam.

Polyrit didn’t have ear-plugs or headsets for us, so after a while, the roaring hum of the machines took its toll. We would later release our stress on the tennis courts, on a horse or from tequila shots late at night. My favorite was riding bareback with Asaf. He didn’t speak English and I didn’t speak Hebrew but we both spoke enough French to communicate what we had to and as for the rest, we simply didn’t need language. We had our horses, the wind against our faces and the beach sand.

Often, the volunteer refrigerator would shut off in the middle of the night. Surrounded by dozens of loud stray cats, the fridge was located at the end of Main Street in between an aisle of rooms. When it went off, so did everything else. There was rarely any silence to our nights so even without the fridge hum, you could hear lizards, rats and snakes in the bush surrounding our rooms, until the cats started hissing which drone out the sounds of everything else . . . that is except for the volunteers’ voices as soon as the fridge died.

It went something like this:

Shaun – FUCK, not again.

Soren – Shut up Shaun, who was pissed off that his ancient Hebrew music stopped playing (he became obsessed with it after living on the kibbutz for three weeks)

From somewhere at the left hand end of the hall – Basta! Basta!

Roberto – Damn cats.

Lauren – Merde. Merde.

Silence.

Mark – Someone go get Claire (but no one ever did).

Maria – go to sleep ya bastards.

Soren – not without my music.

Shaun – FUCK.

Soren – Shut up.

And so it went.

It wasn’t quite the Waltons but we did find solace in each other . . . day and night.

I’d usually wait about five minutes or so before turning on my blue battery operated flashlight and lighting two candles, one was a holy one I bought in Bethlehem and the other, a multicolored one from Berlin which was housed in a Maccabee beer bottle. Once it was bright enough to see, I’d continue to write in my journal or redecorate my room for the umpteenth time with something I picked up along the beach or bartered for from one of the locals.

One day Mark found a huge snake. His voice rose as he used his hands to show how wide and long it was. We all wanted to know if it was alive or dead and where he last saw it. “Not far from the men’s showers,” he said, which was not far from everything. The area was relatively small, so while most of the men shrugged, the women didn’t walk home at night alone until the snake was found. The snake hunt began the next day and it consumed our conversation in the kibbutz pub every night. It wasn’t caught until eight days later, the same morning I discovered two dead frogs under my mattress while making the bed. I added some mesh to my tattered windows, painted my cupboard purple and dyed my curtains blue from one of those cheap kits you’d find in an old fashioned Woolworth back home.

Shortly after the snake incident, I was moved from the Polyrit factory to the fields. Mexican Raphael, Belgian Laurent and Swedish Magnus and Anders (newbies) joined me on the tractor every morning. Mornings were cool but by mid-day, the sweltering sun was beating down on us as we quickly loaded oranges from the trees into a large wooden bin. Notice the old fashioned radio in one of the crates — it was our main source of music and news.

We worked hard and long, so much so that we left the fields each day with scratches on our arms and legs, the blood already dried from a day in the sun. After forty hours each week with thorny bushes and rough branches, my once soft hands became rough and worn.

That said, life-changing conversations over the branches while seeing the golden horizon beyond the treetops fed your soul, so it made the hard work worth it. Ironically, we wouldn’t talk about Israeli politics all that often, but we did talk about American international policy, Apartheid, the Far East, and what was happening in Tibet. Perhaps the internal strife was too close to home for all of us. Remember, Zikim was a stone’s throw from the Gaza strip, so whenever we’d hitchhike to a nearby city or town, it was typically north, not south.

One day, Sybally’s friend kibbutznik Renan asked me to photograph for the kibbutz monthly newsletter and meetings. Renan wanted shots of the cotton fields as well, so I had to learn about irrigation. I also photographed the horses, including the wild ones, the cows, the factories, the picking areas – oranges, avocados, and peanuts. I could choose the time I wanted to shoot, so I always chose the most peaceful hours of the day. Here, I could be lost in the silence and truly focus on my subjects.

Shooting people working inside the factories was the most rewarding. There was something about the way people shut off when they were face-to-face with nothing but a conveyer belt for eight hours a day. For some reason, capturing that nothingness in their faces when they were in that zone was very moving. Sadly, I can’t remember whatever happened to those higher quality images and I left the kibbutz with nothing but the poor quality shots from my cheap camera.

When I moved to kitchen duty, I started developing stronger ties with the Israelis. A few girls my age began to help me with my Hebrew. While I never learned to write or read it, I was able to follow basic conversations by the time I left. I even joined the Hebrew choir for a while but I had cheat sheets to help me get through each song.

Today, the language is nothing but a distant memory, although the occasional word here and there draws me in as if I’m watching an old black and white movie I had seen as a child. While none of them talked about the Holocaust days with us or each other, we drank well into the night while we shared other stories, a bond I fondly remember to this day.

When I went back to Israel roughly 14 years ago, 80-year-old Israeli-born Peter, who has his own remarkable story, offered to drive me back to Zikim. He cautioned me that kibbutzim today are not what they were and many were no longer in operation.

Returning to Israel after so many years was more than a rendezvous with nostalgia. It was 2008 and I was co-leading a group of writers and social media aficionados around the country. My life as a publicist, entrepreneur and blogger met the former me, a teenage girl with a pony-tail on an adventure that helped shape the rest of her life.

According to Peter, who moved to Israel after his parents who fled the Holocaust died in Chile, most kibbutzim belong to one of three national kibbutz movements, each connected to a particular ideology. There were the far left leaning Zionist ones, which were the most collective and Marxist, the smaller religious, ultra-orthodox ones (“dati”) and the social democrat kibbutzim, which is the philosophy that Ben-Gurion apparently supported. Zikim was a far left Zionist kibbutz; many of its members came from eastern Europe and South America. Some were Holocaust survivors or children of survivors. Many never knew their parents but somehow made their way to Israel after they turned 18 as a way to reconnect with the heritage they never knew.

When kibbutzim were first founded at the turn of the 20th century, they were extremely popular as were the strong Zionist movements which formed many of these early Israel communes. Early founders were young Jewish pioneers, mainly from Eastern Europe, who not only came to reclaim the soil of their ancient homeland, but also to forge a new way of life for generations to come.

If there’s one word that might describe the kibbutzim I knew in the eighties, it would have to be community. Everyone was equal and no one had more than their neighbor. Early kibbutzim were rural societies dedicated to mutual aid and social justice and the concept was quite simple. Everything you had went into a big pool which was shared amongst whomever needed it at the time. Sharing chores, children, food and the burdens of everyday life were an integral part of its core belief system. And, no one owned anything. Growing up in the states, this concept was pretty foreign where consumerism has long become the order of the day.

Kibbutz members were assigned to positions for varying lengths of time, while routine functions such as kitchen and dining hall duty were performed on a rotation basis. An economic coordinator was responsible for organizing the work of the different branches and for implementing production and investment plans.

Coming from a country where you could buy whatever you wanted, move around freely, speak up whenever you felt like it and work in whatever profession you chose, I had to know – what would it be like without those options? How would your understanding of the word empathy change? After my own experience, I was convinced every American should spend some time on a kibbutz.

On our drive back to Zikim, it was a fairly warm spring day. Peter spoke to me about kibbutz life from his perspective. From the 1930s to the 1950s, when the Zionist movement was strong, kibbutz life was idealized, then later demonized. Kibbutzim were central to the development of the state; borders were even drawn around them. In 1980, there were roughly 250 kibbutzim scattered around Israel. It was the mid-eighties when things began to shift for a mixture of political and economic reasons (around the time I was there). Many kibbutzim were in debt at the time and volunteers from the West were being turned away because there wasn’t enough work. I was almost one of them.

Peter spoke of the historical transitions. “The worker movement split, and then it split again. Kibbutzism was the only way to really colonize a country at the time. It was a way to teach Jews how to farm land, but this was at a time when there was an idealization of agricultural workers,” he said.

While agriculture was a key part of most kibbutzim, including Zikim at the time, most of them expanded into other kinds of industry as well, ranging from clothing and irrigation systems to metal, plastics and processed foods. The industrial facilities were often small however, with less than a hundred workers, a handful of them non-Israeli volunteers such as myself, at least until the early 1990’s.

Peter was 80 years of age in 2008 so he’d be 95 now if he’s still with us. I’ll still never forget that trip with Peter on the Ashkelon road driving back to my old kibbutz. At the time, he was doing a lot of online research and working on his life story in three languages. He checked his email daily and had a cell phone.

He wasn’t entirely sure where the kibbutz was but we had a map. I didn’t look at one in advance, but as he turned right into Ashkelon, I knew we made a wrong turn. I didn’t pipe up since I wanted to drive through the city. So much had changed that I barely recognized it between the mini-malls, local fast-food eateries and streets full of Russian immigrants who came over in the nineties. Israel took in a million Russian immigrants, 50,000+ of which were engineers. It should be no surprise to learn that Russians have been an important part of the development and growth of technology in Israel.

Once we got back to the main road and headed south towards Gaza, I relived my countless rides in the back of someone’s truck, an army jeep or an Israeli car. It was all so familiar that it felt like yesterday I had sat on the side of that road waiting for a lift. It was remarkable how much I remembered about the Haifa to Ashkelon road yet if you asked me for landmarks on the San Francisco to Palo Alto highway, a route I do frequently, I wouldn’t be able to give you one. This is largely because I was alert and wide awake at all times when I lived in Israel. Every encounter was worth savoring, each conversation a deep one, and all decisions were creations of something new. With very few dollars in my pocket, I hitched everywhere.

We passed signs for Yad Modakhai where we used to go via Forrest Road on borrowed army trucks to watch action flicks with kibbutzniks. A mere three kilometers off the main road was Karmiyya, where Asaf and I rode horses with a view of a wild Israeli sky in the late afternoon. When we saw a sign for the kibbutz on the right, I was overwhelmed with anticipation, excitement, curiosity, and nostaglia, for I didn’t know if I’d find anyone who’d remember me or I them, nor did I know whether it was still in service.

Zikim was quiet as we pulled up and no one was in sight. According to Peter who was a walking history book, many of the kibbutzim are no longer working ones. Some have turned into community centers, they no longer have volunteers and many offspring from the last generation have moved into towns and cities, leaving communal life behind.

I was prepared for that reality, although I jumped out of the car as if I was home, and headed straight for the mess hall. Downstairs in the kibbutz café, the same piano I played so many years ago sat up against the wall in front of two large windows. I ran up to the second floor two stairs at a time to find a short woman in the mess hall clearing buckets of food on a rolling stand. Her English was minimal so I was thankful when Peter made his way through the double doors and shared my story with her in Hebrew.

She smiled as he spoke. As she nodded, I became nervous. Excited. Pensive. My stomach churned as memories flooded my head. After Peter finished speaking, she turned to me and in broken English, asked, “Who do you remember?”

I rattled off a few names before I got to Sybally and then she cut me off — “Ken Ken, Sybally. He is still here.” Since I was so young and considered him more of a grandfather figure . . . a mentor, I wasn’t sure he was still alive. At 72, I would soon discover that he was retired and spent most of his time tending to an extended garden full of vibrantly colored flowers, herbs and vegetables.

We walked through his garden, took photos and shared a pot of tea. I didn’t recognize many of the names he threw my way until we got to Miriam. A light bulb went off when I heard her name though my memory was fuzzy. What did I remember about her? And why?

70-year-old English Miriam lived in the same area so we were able to walk to her house within minutes. Excited and eager to hear all and tell all, we settled in for hours and hours of storytelling, some of which brought tears to my eyes. She took us on a tour through every nook and cranny of the kibbutz, including the road to the beach where we rode horses without saddles and army trucks sat on sand banks not far away. The Polyron and Polyrit factories were both still standing although Polyrit had been turned into a warehouse for mattresses and furniture.

Next to each factory stood a bomb shelter, which sadly had become an integrated part of life for people at Zikim.

We could easily see Gaza less than a quarter mile away. Within such short bombing range, the shelters were not something from a past memory. I asked them when they last used them and Miriam said, “A few weeks ago when a Palestinian bomb went off. No one was injured but we lost seven cows.” Below is the refet area where the cows were hit.

She talked at great length about this new reality in their lives. She also told us what to do if we heard sirens go off. Typically you’d have twenty seconds or so to make it to a shelter. If we were in our car on our way out of the grounds and a siren went off, we should turn the car off, get out of the car and run as far away as possible.

Below, looking toward Gaza:

Part of the Polyrit factory produced service hatches for banks and clinics in 2008. We drove past the factory and a small grassy area with dried flowers, brush and weeds. A man who made cement for a living rented part of this land. Here, I noticed the electric fence I didn’t recall from two decades earlier. Just beyond the fence, I could clearly see Gaza. Peter’s grandson was working in Sderoth at that time, a town south of Ashkelon, which was apparently receiving most of the rockets. Despite this fact, Peter’s attitude was empowering and he exuded gratitude, not fear.

Below, additional buildings they also used as bomb shelters on the grounds.

Near the electronic fence sat Zikim’s graveyard. When Zikim settled in 1949, the area which now houses the graveyard belonged to Arabs. The day before we arrived, two Israeli civilians were injured and one soldier was killed by terrorists. The Palestinian attackers were apparently also killed.

The cow sheds were as I remembered as was the road leading to Main Street where I spent so many reflective nights transitioning from girlhood to womanhood. Apparently, I missed seeing Main Street in close to its original form by only six months. Bulldozers and tractors uprooted the area and none of the worn wooden sheds were left standing. According to Miriam, they were building condos that could be rented once the project was completed. I mourned Main Street even though an overhaul was clearly needed. I sat there for quite a while recollecting whatever memories I could muster from so many years ago. Miriam and Peter understood my need to be alone, although I hoped I wouldn’t run into a massive snake.

White washed buildings with steel windows were the children’s houses, all of them reinforced and used as additional bomb shelters.

When we finally sat down again and the tea kettle was boiling, I listened to Miriam’s life story. Through art therapy and visual memories that came out in the final days of her older sister’s life, she recounted her childhood days in eastern Europe, before her mother sent her on a boat to England. At age five, it would be the last time she would ever see her Jewish parents.

She remembered the black boots, which were likely eye-level for her at the time. Miriam was on the last ship to set sail with Jewish refugees from Holland in 1939. She was part of what became known as the kinder train children, and she was also one of only 100 who made it safely to British soil via ship. She has no memory of her mother’s face and only one worn photo of her father, which she incorporated into a painting she calls Sleepless Nights. (if you look carefully, you’ll see the inserted photo of her father on the left)

Like many Holocaust survivors and children of parents who were killed in the Holocaust, they never spoke of their memories – with each other or the next generation. Only after a life crash was Miriam able to share her story.

If you look at the painting below entitled Sunflowers, you may notice tiny worms inside the flowers which came from a memory on the boat where children were given crackers with worms to eat.

Zikim took in hundreds of Russian immigrants around 1994. Miriam explained, “We built caravan and mobile homes for them to live in for a year so they could learn to speak Hebrew. Most didn’t want to stay for good. Communal life reminded them too much of what they just escaped from.” The majority of them apparently settled in towns like Ashkelon just north of Zikim, where we spent many a day off years ago.

There was also a large English immigration. She recalls, “Zikim kibbutzniks performed a play and held a party to celebrate their coming.” Miriam came as part of a large Zionist left wing movement when she was about 19 years old from the U.K. “We were so idealistic,” she said with a nostalgic smile.

She continued to share her memories.

“There have been a lot of changes along the way since the ‘Children of the Dream.’ I came with a nice coat I bought in London before I left. The kibbutz took my coat to be used as the travel coat so that all kibbutzniks could use it when they went into town or somewhere for a special occasion.”

“How did you feel about losing your only coat?” I asked.

“It was all worth the sacrifice for the greater good and a better way of life,” she replied with a warm grin.

As we talked for hours, I traced every movement in her face and the glossiness in her eyes. I absorbed the artwork scattered around her house bearing dark names. I looked at photos from the children’s home in northern England where she spent the forties and part of the fifties. Then, she moved to Israel while she was coming-of-age. Just like me but for very different reasons.

The result was the same for both of us. Miriam found shelter, comfort and tranquility in a place where she could be lost but also found. She was embraced by these wonderful giving misfits, just like the misfits who embraced me at Zikim thirty years after she arrived.

It’s extraordinary when people who appear to be poles apart come together and can rediscover their souls again as we did on that memorable day. There’s that special moment when you sit quietly and reflect, only to realize it may be a rediscovery through the same heart and pair of eyes. The interconnectedness of us all, finding a familiar thread and frequency that resonates. Words that feel true. Eyes that lift your spirit. Hands that heal with a touch. An embrace that feels like home.

Yes, this is exactly why we are brought together to share in every precious moment that comes our way, the kind you can never explain with words. Only then do you realize that we truly do come from the same place, the same force, the same life energy. These encounters show up to blow your soul wide open so you remember the oneness of all of us. Our shared history. Our shared humanity.

This article, which ultimately turned into a short story, was written in 2008, but updated in November 2023. With the tragedies and killing continuing to happen between Palestinians and Israelis, I have been keeping these precious memories at bay over the last several weeks. That is, until I heard from Shaun last week. His message prodded me to revisit this recollection I wrote nearly 15 years ago.

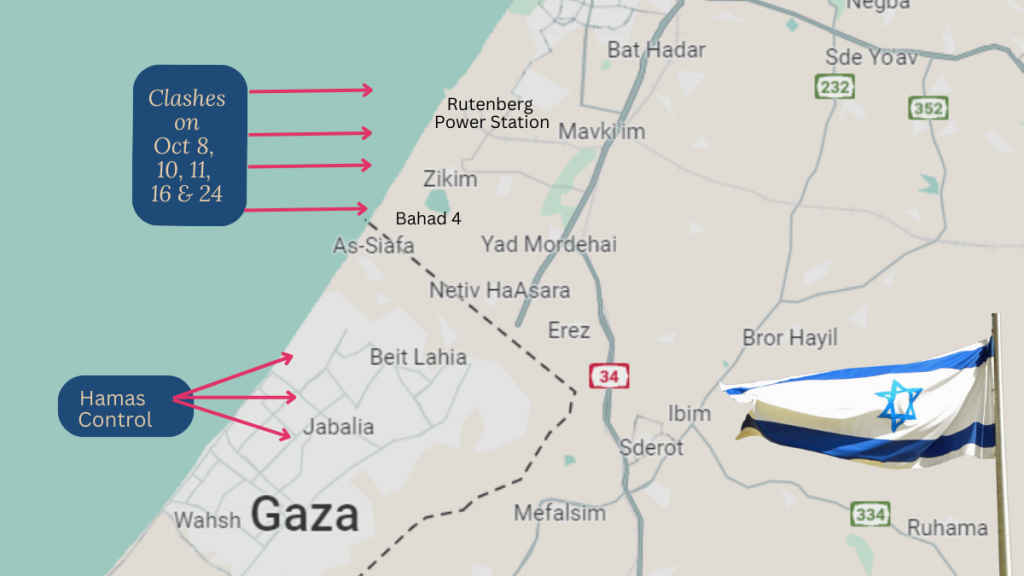

Shaun and I have managed to stay in touch for many years before cell phones and email, a remarkable feat. We even traveled together for a while in Kenya and Ethiopia in the 1990’s. Today, we can text each other; his most recent outreach came via a Facebook ping. It was entitled “The Miracle of Zikim.” You see, Zikim sits in the middle of the battle, so much so that there’s a Wikipedia page for “The Battle of Zikim.” It started when Hamas launched its attack from the Gaza Strip on October 7 and the subsequent fighting occurred in and around Zikim, which btw doesn’t just include the kibbutz anymore but also the Bahad 4 military post, a training base for Israel Defense Forces (IDF) recruits. Notice roughly where the October attacks and clashes happened on October 8, 10, 11, 16 and 24. Although the arrows can’t be precise on a reduced sized map, it gives you an idea just how close to Zikim the battle is taking place.

There she is – Zikim, in the middle of so much current strife. It broke my heart to see the locations and hear about the atrocities. Are Miriam and Sybally still alive? I can’t know for sure about them or any of the others I sang, danced, hiked, ate and drank with until the late hours. Asaf who I spent most of my time riding horses with was my age at the time and without a surname, it would be next to impossible to find out where he is and what path he took.

How many of you are growing tired of network TV debates and experts sharing their opinions? Is it serving you or merely creating more anxiety?

You know, as an avid traveler who has been to 90 or so countries and resided in ten of them, I’ve experienced people’s lives far and wide. Like Zikim’s Main Street, I’ve lived in African towns where water was also scarce. I’ve camped on the banks of Lake Malawi where I nursed my ex-husband back to health after a bout with Malaria. He recovered, but not everyone we lived amongst were so lucky because they didn’t have access to the same resources. I’ve spent weeks staying in tiny villages in Southeast Asia and was bed-ridden for nearly two months in northern Nepal after Hep A took us down while trekking through the Himalayas on elephant. We too survived this but met many families who lost loved ones to the very same ailments. Many didn’t have access to fresh water.

I’ve lived in South Africa in both a pre-Apartheid and post-Apartheid era. In the 1980’s, I snuck into Soweto in the trunk of a car, eager to hear black South Africans’ truth. It was a far cry from the stories I heard in Hyde Park, one of Johannesburg’s wealthier suburbs where I went to high school for a year. How many knew about the tragic deaths in prisons, the illegal arrests and the corruption? I’ll never know, but they never had to deal with smoke bombs as they sipped their champagne and ate their strawberries with cream. As I made my way through countless ritzy barbecues and parties in well-manicured backyards with massive swimming pools, I could see the smoke in Soweto off in the distance.

I taught English to Kenyan girls on an island off the coast of Mombasa and lived amongst them, hearing their stories day after day. They didn’t use a Colonial map when they learned about Africa or history in general, something that wouldn’t occur to most Europeans or Americans. I didn’t even recognize some of the names since I had been conditioned and schooled under a white man’s umbrella. It was an eye opener. They certainly claimed a different truth than the one I have been programmed to know.

Trying to survive in London during college and for many years after, I worked in so many pubs I can’t count them all. Many were multicultural and so were the visitors, all with their own stories to share. They had their own pains, sorrows and nightmares. One day after taking the escalator up to the ground level from the Tube, a bomb went off and people were killed. It was the IRA and I missed it by minutes and have heard similar stories from those who left the Twin Towers minutes before it went down. So many innocents get caught in the wake of terrorism and war.

I’ve met Palestinians along my travels who have also lost family members, children, even babies. I’ve heard the heartache on both sides and yet, when I mentioned the fact that Palestinians have also faced tragic losses and they too have their own perspective, someone took it as offensive. Hamas doesn’t represent all Palestinians just as ISIS and the IRGC-QF don’t represent all Muslims.

I merely mention these cultural experiences because one thing I’ve learned over the years trekking around the world and living on foreign soil, is that we can’t possibly know what’s in the head of another. We don’t know their stories, their truth. What is the trigger that moves someone in pain to someone who joins a terrorist group?

We all carry wounds, griefs and conditioning, all leading to hard-coded beliefs about others and who we think they are. We’re not even always aware of our own biases and wiring as we make our way through life. Ultimately, our beliefs are merely perceptions. Memories plant seeds and those seeds carry pain, some of which leak out in unhealthy ways.

There’s no question that I share a special bond with Israel despite the fact I’m technically not Jewish, at least not in this lifetime. But I’ve lived there. I have shared wine, food, tears, horses, stories, dances, gardening, theater, art, music, cats and tequila with Israelis and Jews who found their way to the kibbutz I too called home for a time. I’ve worked in factories and fields with them, the very same fields that are currently getting bombed. I cried as they mustered up the courage to share their Holocaust stories. I did pro-bono PR for the Israel Conference (based in LA) and led a technology group to Israel to cross-pollinate tech ideas and elevate start-ups. I’ve had several Israeli clients over the years, some of whom have lost children to war. I’ve worked with Israel investors and gone to my share of Israeli events. The list goes on.

So, how do I feel when I hear about the situation in Israel?

I feel the same way many people do I imagine: “It’s atrocious. It’s sick. Enough already.”

Each side is glued to a story about who is right. Who should win. Who should have the power. Who should “own” the land. Fighting over beliefs about land and religion is far from new – it’s been like this for millennia and beyond, but we are all living in the here-and-now. Dealing with the news every day. Disgusted by the articles. The TV visuals. The commentaries. After a while, it makes us nauseous. Sadly, news is often designed to polarize us.

Every group has their own histories, their own memories and their own truths, just like the Kenyan girls, those living in tattered shacks in Soweto, the terrorists in Northern Ireland, and the Taliban who have turned back the hands of time once again for women in Afghanistan. Because everyone’s truth is their unique perspective, all of it is valid. It all must be valid if we are to truly hear one another’s inner screams and then try to understand them. Empathy comes from this place of inner listening. We can hear our own voices in the melding of that inner listening, aching to be understood just as they ache for the same.

We invite in cooperation and unity when we surrender to love. We surrender to a higher vibration of being. To peace. This is the path to a higher and richer collective consciousness. It is here where we must set the intention, not about who is right or wrong. Not about God, Allah, Elohim or Yahweh, but about peace. About love. That we can live together in harmony.

The moment we all realize our interconnectedness, our swords will rise no more. What we do to another, we do to ourselves and the pattern repeats itself again and again. Like a hamster wheel. With this universal realization, the peace we become will be the peace we shall reap. It’s time and it’s long, long overdue.